By Michelle A. Tisdel, Ph.D., Social anthropologist

In the summer of 2020, millions of people worldwide protested after police officers in Minneapolis killed African American George Floyd May 25. Afrikans Rising in Solidarity and Empowerment (ARISE) and the African Student Association at the University of Oslo (ASA) took initiative to the demonstration in Oslo June 5, 2020. The protesters gathered outside by the U.S. Embassy and marched down to Eidsvolls Square in front of the parliament building. Despite the Covid-19 restrictions, more than 15,000 people participated.

Anti-racism, Freedom of Speech, and Collective mobilization

ASA and ARISE were already planning a joint campaign about racism at the University of Oslo when the news of Floyd’s murder spread. They agreed to organize a demonstration that would also focus on the situation in Norway. The killing of Floyd became a symbol of racism as a larger global problem — not just as a problem in the USA. This was the message behind the demonstration “We can’t Breathe: Justice for George Floyd.

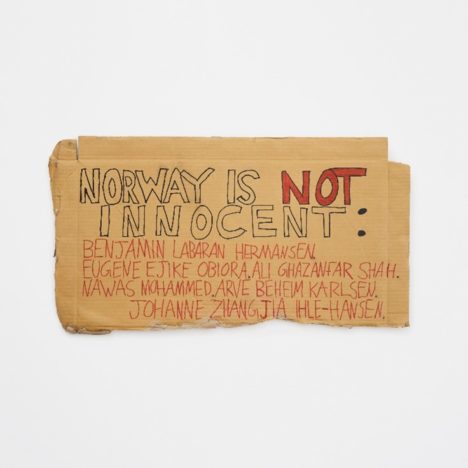

Because even though this was a solidarity demonstration for George Floyd — the demonstration was called “We Can’t Breathe.” We also had posters of Eugene Obiora who was also strangled to death by the police here in Norway, in Trondheim.

Demonstration organizer Mohamed Awil [1]

Protest is a form of political action and a language of expression. That protesters act together and exercise their freedom of speech, shows the amount of support there is for a cause in society.

The demonstration is a part of a history of anti-racism and political mobilization for equality that minoritized Indigenous, immigrant, national minority, and “Black” communities have led in Norway. This is the message driving the exhibition Your Breath, Your Voice: Unfiltered expressions about antiracism and the demonstration June 5, 2020, which opened Museum of Oslo October 18, 2022.[2] The title is inspired by the speech of author, poet, and protest speaker Guro Sibeko on June 5, 2020.

If you have breath, let it become a voice. Remember – it has also happened to us here at home. Demand justice for Obiora! We are not allowed to forget!

Your Breath, Your Voice: Unfiltered expressions about antiracism and the demonstration June 5, 2020

I initiated the documentation project Lift Every Voice (LEV) June 6, 2020, to collect posters from the demonstration in 2020. As a social anthropologist and researcher of heritage production, I regard the protest posters as emblems of demonstrations and biographical objects of the protesters. Each poster is a memory object that contributed to the collective message of the demonstration. In 2021 and 2022, LEV and Memoar organization for oral history led a team that conducted oral history interviews, in which protesters reflect on what it was like to be part of the demonstration.

The protest demonstration transformed Eidsvolls Square into a “contact zone,” a social arena where experience and histories met but also challenged and clashed with each other. For some people, the murder was a reminder of their own experiences of racism and injustice here at home in Norway. It just confirmed a well-known problem. For other demonstrators, the murder of Floyd led to a new awareness.

Floyd’s murder and the demonstration were “critical events,” moments that created new ways of understanding racism and historical inequality. A critical event can create new references, understandings, and connections. The new dividing line marks a “before” and “after” the actual event.

“Receipt Scheme” – Stop ethnic profiling!

Before the demonstration, the initiators ARISE and ASA organized a signature campaign with a call for a Kvitteringsordning or receipt scheme that police would use when they stop and search people. Their goal was to contribute to the advocacy work to end discriminatory stop and search practices and ethnic profiling, which Akhenaton de Leon and the OMOD Centre for Social Justice (OMOD) had spearheaded since the 1990s. This is an example of the Norwegian Conditions that the museum exhibition discusses.

Before the Critical Events of 2020

Other relevant examples of demonstrations and collective mobilizations for anti-racism include a solidarity protest march in Oslo in 1963 following the March on Washington during the Civil Rights Movement in USA. More than two thousand people participated in the Oslo-demonstration led by the Foreign Workers’ Association in 1976. There were several protests between 2006 and 2008, to demand justice for Eugene Ejike Obiora. He died September 7, 2006, after the police in Norwegian city Trondheim restrained him. The police used a chokehold and held Obiora down during the arrest.

Since 1993, OMOD has lobbied and put ethnic profiling in Norway on the agenda. OMOD has advocated for control data and submitted proposals to the justice sector for a “receipt scheme.” OMOD’s co-founder and director Akhenaton de Leon explains the purpose of a receipt as control data:

Everyone who is checked by the police, regardless of background and type of check, must receive a receipt as documentation. In this way, it would be ascertained whether the “stop-and-search” checks discriminate against certain groups, and whether there is a need to change the police’s routines.

Ethnic profiling involves discrimination based on skin color or ethnicity, and therefore people can regard it as a form of racism. There has been no requirement that the police document their random “stop-and-search” control activities. OMOD and other advocates argue that it is time for more Police accountability.

After the Critical Events of 2020

A week after the demonstration, ARISE, ASA and the OMOD delivered a letter and petition with over 27,000 signatures to the Ministry of Justice by Minister of Justice Monica Mæland and the Storting (Norwegian Parliament). The petition asks the state to reconsider Section 6 of the Police Act on the police’s use of force. In the letter, dated 12 June 2020, they write:

“We need documentation for inspection now! We must ban the use of neck holds now! […]”.

In November 2021, the Storting decided that the receipt scheme should be tried in the Oslo municipality for a trial period.

The purpose of OMOD’s proposal for the Receipt Scheme is to obtain relevant data that can shed light on the extent to which there is a connection between the police’s control practices and experiences of ethnic discrimination. For OMOD, data is important for policy development, prevention of ethnic profiling and creating more trust between the Police and citizens.

The police’s pilot project with the Receipt Scheme began on 5 December 2022 and will last for nine months until 3 September 2023. The police have decided that the receipt should not include or record information about ethnicity, skin color or immigrant background. On its website, the Police explains the intention of the pilot project:

The intention of the trial scheme is to obtain knowledge about how a receipt scheme works in practice, how the scheme affects trust in the police, and how it can affect the police’s working methods.

Thus, during the pilot project, the receipt will contain information such as name, date of birth, time/place, authority for the check and information about which official (service number) has conducted the check.

Currently Norwegian authorities do not collect information about ethnic background due to personal privacy, concern for civil liberties, and fear of the misuse of such sensitive information. The Police sites these reasons for excluding this information from the pilot project. Critics of this decision, however, site lack of interest in tackling the issue of ethnic profiling and structural racism.

The Norwegian Association of Lawyers’ Inclusion and Diversity Committee, which was in a working group about the project at the Oslo Police District, asked the Oslo Police District to seek external expertise to investigate how to register such sensitive information. “The Police has not obtained this information externally or internally via their specialist groups,” according to Halvard Øren, head of the association’s Inclusion and Diversity Committee.

Seeking Equality and Police accountability after 2020

Anti-racism is based on the principles of human rights and equality before the law. The government acknowledges that racism can affect the quality of life of those affected.

Racism and discrimination have negative consequences for individuals, groups and society as a whole. […] Exclusion, lower social mobility and psychological problems can be consequences of racism and discrimination for the individual.[3]

OMOD and other relevant actors argue that the Police’s trial project could work against its purpose. Moreover, excluding background information creates a poor starting point and insufficient data for further work against ethnic discrimination. Critics note that the scheme could increase distrust between the police and citizens in the post George Floyd-era.

For OMOD, ASA, ARISE, and other supporters of the Receipt scheme, the new pilot project signaled the beginning of a mutually beneficial process for the Police, antiracism advocates, and citizens seeking to eradicate ethnic profiling.

The demonstration on June 5, 2020, was not the first time that people gathered to protest racism in Oslo. It is unlikely to be the last time. As the museum exhibition discusses, although the demonstration was successful as a collective mobilization, it did not create the desired reckoning with racism that many demonstrators and the organizers ARISE and ASA desired. “Many people think that racism was something we finished with a long time ago, but really we have never had the courage to take a proper stand,” as Mohamed Awil from the African Student Association (Univ. Oslo) told the newspaper Universitas in 2020.[4]

—-

[1] Interview (2021) for the exhibition Your Breath, Your Voice.

[2] The documentation project Lift Every Voice (LEV) and the online journalism magazine The Oslo Desk (TOD) took the initiative to the exhibition project in collaboration with Memoar, the Norwegian organization for oral history. The project is a collaboration with Oslo Museum, and the exhibition catalog producer is Transcultural Arts Production (TrAP).

[3] The Norwegian Government’s Action Plan against Racism and Discrimination on the Grounds of Ethnicity and Religion 2020–2023, p. 11. The Norwegian Government’s Action Plan against Racism and Discrimination on the Grounds of Ethnicity and Religion (regjeringen.no)

[4] Universitas, August 12, 2020 https://universitas.no/sak/67144/de-storste-sosiale-bevegelsene-har-kommet-fra-univ/